Archive

Debt Management to Become a Standalone Course in High Schools.

Come on, it might as well be.

Lord Browne and his team issued a report on October 12th detailing the direction higher education must go because of this economic climate. We have just seen a defence review today which is cutting 42,000 jobs in the Ministry of Defence, affecting RAF, Navy, Army and civilian positions. Where do they go? Who cares! Oh, you do.

The country is on a downward downsizing spiral because of the gluttony and risk taking from the guys at the top.

Our education system has long been identified as a sector in dire need of reform, yet has gone without the attention it deserves because of the turbulent decade we have just experienced. We have been involved in two messy wars, terrorism on our shores and endured a recession so huge the effects will be felt for many years to come.

What do we know about this system which is responsible for moulding the next generation of workers, thinkers, innovators, and moralisers? Its benefits include a tuition fee cap that normalises the financial circumstances in which one can enter higher education. Then there are drawbacks, such as the rigidity of assessment procedures and the linearity of teaching.

Browne’s report aims to address the impending spending cuts which will affect higher education institutions. The cuts, which will be announced formally tomorrow, will severely squeeze an institution’s funds for teaching and research, so the impetus is on the universities to generate their own funding through private means.

I agree with the purpose of this report – to reform higher education, and later hopefully secondary education – but this effectively means the marketisation of the higher education sector.

This is a kind of a big deal. For a country which did not even charge students tuition fees a little over 12 years ago, we have rapidly got to the point where we are thinking of removing the fee cap altogether. How can something as important as a fee cap, in terms of contributing to social mobility and offering something towards building a true meritocracy, be scrapped?

System not responsive to the changing skills needs of the economy.

Analysis from the UKCES suggests that the higher education system does not produce the most effective mix of skills to meet business needs. 20% of businesses report having a skills gap of some kind in their existing workforce, up from 16% since 2007.The CBI found that 48% of employers were dissatisfied with the business awareness of the graduates they hired. This evidence suggests there needs to be a closer fit between what is taught in higher education and the skills needed in the economy. It also adds force to the argument for helping existing workers to enter part time study and improve their skills.

Securing a Sustainable Future for Higher Education in England, p.23

On the face of it, all this means is that higher education must adapt to the business market and provide a business friendly skill-set. This is one of the underlying assumptions of this report, and one which it is guided by the will to massage the various business interests which would like to see students develop skills the businesses want.

This is vitally important. The question which is ignored in this report, and any report which first considers the requirements of current short-term gains focused business first, is what should be dictated by what? Should what we study determine the jobs which are created, or should the existing jobs created by existing managers determine what we study?

Again, on the face of it, it is ridiculous to consider someone graduating from a philosophy degree starting a career as a full-time philosopher. However, isn’t it equally as ridiculous (to add very unjust) for someone who has an incredible grasp of history to enter employment as a sales representative, assuming that isn’t their burning desire?

Business can never be allowed to dictate our education because a homogenised education system, i.e. one tailored to meet the demands of business, will destroy diversity and positively halt innovation, condemning us to endlessly trying to meet unrealistic targets which exist in some areas of the working world.

What about employers who value employees with unique skill and knowledge sets, who are able to contribute creatively, rather than mechanically?

But no, lets roundly blame the beleaguered education system for not producing them while largely ignoring the employment market which does not welcome them. Schools are flooded with restrictive paperwork from the government while university leavers have to endure the rhetoric of business interests. We are being made to focus on only one of the two fronts.

Quality.

Students are no more satisfied with higher education than ten years ago. Employers report that many graduates lack the skills they need to improve productivity. Institutions have no access to additional investment to pay for improvements to the courses they provide. In any case the incentives for them to improve the student experience are limited.

p.23

Why is that? Well, it is easy to see that the blame for a graduate’s frustration falls squarely on the institution or course he has just left, either by misinforming him about prospects, or teaching him self-indulgent skills which are not easily transferable. We never really look at the employment sector to identify the great disconnect between it and our education too.

Business must be put in the spotlight. Also, we must stop using the word “economy” interchangeably with “business” in the first place, as, rather cannily, “economy” seems to have this more inclusive connotation, whereas “business” seems to describe some arbitrary organisation apart from the consumer, and crucially, with little interest in the consumer.

All in all, just another marketing ploy the government and big business utilise to dull our sensibilities when faced with their simplistic solutions (to their problems). Before even looking at the outrageous numbers, the first principle underpinning this report fails quite astonishingly:

Principle 1: There should be more investment in higher education – but institutions will have to convince students of the benefits of investing more.

p.24

I have emboldened the word “convince” not only to draw attention to it, but simply to underline it’s boldness. Students evidently are not willing to pay any more for their education, but will be powerless if universities impose higher fees to generate funding. There are a lot of problems with this strategy, never mind the numbers it entails.

Firstly, government officials and the people who are behind this report actually believe universities will give their persuasive efforts some meat and backbone. Persuasion can always be simply that: persuasion. Convincing a student of the supposed benefits of studying at a particular institution could merely accelerate the growth of the universities’ marketing arms.

Secondly, every university already outlines, in paper with a high GSM, that they are incredible and innovative. Giving a university the freedom to raise prices like a business will negatively enable it to behave like a business in other areas. Costs will be minimised regardless of quality of output, and prestige will play even more of a prominent role than it already does.

“Increasing competition for students will mean that institutions will have stronger incentives to focus on improving teaching quality.”

p.48

Creating “competition for students” through a private market would be catastrophic for society on many levels. Incentivising universities with a profit motive will see profits increase at a rate disproportionate to the standards of education. When taking into account matters such as social mobility, vast debt, and regional insensitivity, the new model leaves a lot to be desired.

Browne’s report models fees up to £12,000 per year, with fees in the region of £6,000 being earmarked as the most common sum to be requested. However, they concede there would be no cap (music to the Russell Group’s ears). It is also conceded that for most universities to break even, fees in excess of £7,000 would need to be charged.

The government, the group who have produced this review, and the universities have all remained relatively tight lipped about the ramifications of removing the cap. Of course they would! The government can make savage cuts, the universities are given the freedom to extort their students, and the this group can add a popular report to their portfolio.

Everyone wins! Except us, as always. Lets live the nightmare for a moment:

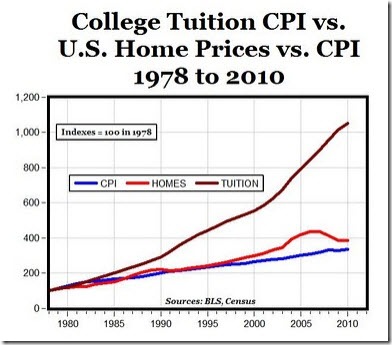

To illustrate what removing the cap could (and most likely would) do, I have obtained a graph with data from the Bureau of Labour Statistics in the U.S. Browne’s review and the support it has drawn from the coalition government is explained by satisfying all the parties except the new generation of students.

By adopting more of an American model, we are in danger of letting universities, the crucial institutions which (should) shape employment, innovation, and aid social mobility, concentrate on boosting profits, employing even more administrators to do so, and lumping students with horrendous mortgage style debts before they have even begun their careers.

The mantra of it being an investment for the future is unravelled by our economic cycles of boom and bust which entail little or no job security. Our volatile economic climate is controlled by business interests, and the governments elected to appease them. Employment is slashed at whim, while credit ratings are protected religiously by incompetent regulatory systems.

My cynicism is informed by our neighbours across the Atlantic, whose free market dogma has revealed itself to be a bitter pill to swallow for society at large. Institutions such as Harvard charge as much as $50,000 (£34,000) a year, over 4 years, not 3. The total comes to $200,000. How is this justifiable, other than by regressing to matters of prestige?

George W. Bush, probably the most incompetent president in recent history (and beyond), attended Yale, a renowned university in the U.S. How? Through heavy private contributions – the same contributions we are going to be asked to make to fund our institutions. That’s fairness right there in all its star-spangled glory.

Now, I don’t know about you, but I am not keen for us to produce clowns like that, reassuring English accent or not.